Retention Review

The Retention Review is our quartly publicaiton, a jurried pulication of some of the best that internet philosophy has to offer. If you are interested in submitting to future publications, please email us at editor@aopcar.com.

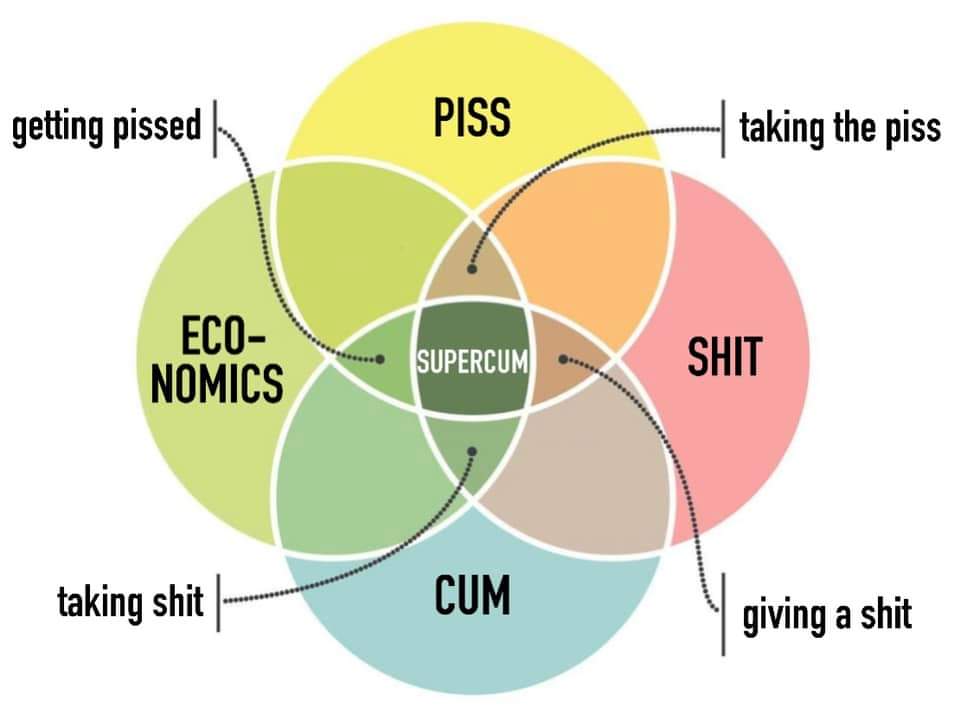

Below you will find The Retention Review Vol. I: Shit, Piss, Cum, and Economics.

PDF download here

Retention Review: Vol. I Shit, Piss, Cum, and Economics

The Case of the Dried ShitstickJavier Milei and Argentina's (re)discovery of Angloperonism

Bicycle

Satire Ad

10:30pm - Pink Flamingos

Stop Fucking Reading

The Sacrifice

Lost in Translation

Kant's Schizophrenic Interrogator, Mirecea Cartarescu

In May 2021, several of my friends and I from the now defunct Facebook group “The Barrel” decided to start a Discord server called Philcord. Over the past three years we have tried—and failed—many times to create a piece of para-academic media that showcased our unique approach to philosophy. Retention Review is the culmination of our hard work.

In May 2021, several of my friends and I from the now defunct Facebook group “The Barrel” decided to start a Discord server called Philcord. Over the past three years we have tried—and failed—many times to create a piece of para-academic media that showcased our unique approach to philosophy. Retention Review is the culmination of our hard work.

Inside this volume you will find philosophy, poetry, short fiction, and literary criticism—informed by the forces that actually dictate our lives: shit, piss, cum, and economics.

Thank you for joining us on this journey and here’s to many more editions in the future.

- Jigme

Editor-in-Chief, Retention Review

The Case of the Dried Shitstick

By Chelsea

This koan appears in a classic collection known as The Gateless Barrier (無門關) compiled by Wumen Huikai, as translated by Robert Aitken:

雲門、因僧問、如何是佛。

A monk asked Yün-men, “What is Buddha?”

門云、乾屎橛。

Yün-men said, “Dried shitstick.”

The point isn’t to figure this one out. It isn’t meaningless, it isn’t beyond our access, but it also isn’t conveyed through words and concepts. Koans emerged in Tang dynasty China as commentaries on the sayings of old Buddhist masters. Within Buddhism, koans are a practice, and not a lot can be said about koans as koans without reference to the practice itself.

By the time Wumen compiled The Gateless Barrier in the early 13th century CE, there had been major developments since koan collections first emerged. On one hand, many monks came from the educated literati that was growing under the Song dynasty, and on the other, a distinguishing feature of Chan/Zen has been its emphasis on a mind-to-mind transmission of the dharma, without reliance on words. Objections arose to koan commentary as a literary exercise, developing apart from spiritual practice. Dahui Zonggao, born a century before Wumen and a member of the same Linji school, went as far as to burn the printing blocks used to publish his teacher’s koan collection, The Blue Cliff Record, out of a concern that it was holding students back. Dahui was, however, a proponent of a new form of koan practice, a sitting practice using hua tou (話頭) or “word head.” An example of a hua tou is within this koan: “dried shitstick.” What is “dried shit-stick”?

The transmission of Buddhism to China brought many concepts, including what is called in Sanskrit the śalākā: a small wooden rod for wiping ass. The Chinese had invented toilet paper by the 6th century CE, but it wasn’t very soft, and shit sticks stuck around. Anyhow, the koan isn’t arbitrary–Yün-men wasn’t just talking out of his ass. But the point isn’t to conceptualize, or to attach a fixed meaning to the shit-stick. To practice using a hua tou is to keep it in mind, to be aware of it, to interrogate it, and to ask where it’s coming from. In a sense, it’s a practice of awareness, no diferent from awareness of the breath.

It’s well-understood that one aim of koan practice is to overcome dualistic ways of seeing the world. The dried shit-stick is a mundane object resulting from the everyday process of digestion, but it invites aversion. Still, if it were as easy as telling yourself, “I must leap over the dual tendencies of attraction and aversion,” the Buddha would’ve had no reason to leave home. Intellectual understanding alone doesn’t amount to practice and realization. A koan doesn’t work through intellectual understanding, but it can provide a basis for practice. The contemporary teacher Guo Gu says in a commentary on this koan:

Similarly, you’re a human being. What is it like to be a human being? Are you living fully as a human should? Are you deluded by your life? What is governing your life? Is it greed, hatred, ignorance, arrogance, and suspicion? If it is, then aren’t you just a puppet held by the strings of these vexations? Until you can break through the shell of self-grasping, you have to ask silly questions such as “What is buddha?” or “What is a human being?” or “A dry shitstick?” without using your intellectual, rational thinking, biases. Instead, the key is earnestness. (From Passing Through the Gateless Barrier: Koan Practice for Real Life, pp. 203-4.)

As with all cases in this collection, Wumen left a commentary. His commentary on the first case, regarding the dog’s Buddha nature, is about as generous as he gets, directly laying out the sort of koan practice he intended for students to pursue. As for his commentary on this one, different translators give it varying treatments. Robert Aitken’s translation is as follows:

It must be said of Yün-men that he was too poor to prepare even the plainest food and too busy to make a careful draft. Probably people will bring forth this dried shitstick to shore up the gate and prop up the door. The Buddha Dharma is thus sure to decay.

Javier Milei and Argentina's (re)discovery of Angloperonism

By Tanasinn

Translated from the Spanish by the author

In the face of exasperated disbelief, a feeling that every generation of Argentines is well acquainted with, a commonplace expression is to state that everything in Argentina is "a joda grande como una casa.” In true lunfardo dialect, "joda" can't quite be easily translated as "joke" because it also carries the meaning of something that should be taken with levity, which doesn't warrant a serious reason of concern - after all, none of Argentina's historical adversities (from weekly inflation rates which would make any sensible person in the Northern Hemisphere blush, to full-blown dictatorships that in the present day no self-righteous gringo would miss tweeting about for months on end) have failed to decimate the Argentine industrious resilience. In proud comparison with cockroaches, the average Argentine is confident that the country and its people will survive nuclear hellfire. After all, everything that happens or could possibly happen in Argentina is a joke as big as a house. Thus, the victory of a literal anarcho capitalist candidate -the wet dream of embarrassed ex-redditors and various online creatures from "serious" countries-, is not all too surprising for the average Argentine. Where else but in Argentina?

Milei's strained ballotage victory, then, came as a surprise mostly only to a very particular subset of Argentines: mainly, those who benefited the most by being yes-men of Alberto Fernandez's late stage Kirchnerist term without any tangible benefit other than self-righteous virtue. One can understand the state worker whose livelihood depends on which party is at the helm of his local town council and how any obviously artificial militancy against Milei may come merely under duress, but not so much the fully-urbanized Porteño of the Palermo-Caballito axis who thanked the government for their utmost care for the people during the Covid lockdown measures and, in the same breath, justified the same government that rerouted the first batches of the vaccine directly to themselves and their relatives. The same group of urbanites who, after four years of self-denial have gone on to make Instagram posts about being part of "the Resistance'' - yes, in the same Marvel undertones you'd find in those who would wear one of those horrid pink hats at the doorsteps of Pennsylvania Avenue. For the remaining half of the country that voted for Milei, on the other hand, it has mostly felt like an inevitability.

Peronism, on the other hand, is now facing its biggest sin: It has lost 50% of its historical electorate in an act of perfidious betrayal of the working class (whatever this means for them at this point). While in no way I can reasonably pretend that this group of bourgeois urbanite "wokies" put the final nail in the Peronist coffin, the peri-electoral haughtiness of this group was so palpable that it's tempting to think about just how badly have they alienated, under the guise of "allyship", an entire voting base from a social stratum sitting so far away below them that it became easier to tokenize them than understanding them. The strength of this group comes not only from tacit validation by the institutional spheres of also from the way they have installed themselves in all forms of mass media: from the classical soapboxing well within pro-government TV and Radio groups to the head-start they had in gaining a foothold in various vertices of social media which, up until very recently, were gatekept by both technology and the English language. In the end, this group provided the same sort of insult to the rest of the country that the Neokirchnerist coalition government did during the past four years: the barefaced pretension that the economic crisis plaguing the country for the better part of a decade was not their fault. The Argentine is accustomed to being aggrieved, but will not tolerate being mocked; the Argentine will shoulder the 170% yearly inflation rate and roughly 50% of its compatriots living below the poverty line, but will refuse to entertain the idleness of a Government that spent the last leg of the race in pretending the problem could be fixed by digging a deeper hole.

This should be somewhat familiar to those with a modicum of observation. To some, certain parallelisms to US politics will become almost self-evident - but perhaps not in the way one may imagine at first.

"Everything in Argentina arrives five years late" is a rule of thumb that allowed some degree of prediction of attitudes and trends in the country's society. This "five years late" statement extended from technologies (like the speeds of broadband internet) to the social topics du jour. Hipsters weren't really a thing in Argentina until well after they went extinct elsewhere in the Great North. Twitter in Argentina was largely confined to a group of US-philic urbanites until a few years ago, in the same way Twitter in the US was largely confined to a group of tech nerds until mockery around the time shortly after Gamergate, whereas Argentines online developed their newfound obsession of gender-neutral language around the end of 2018.

A strange inversion of this occurred in 2016, where you could say that the Argentine ideas of populist third positionism arrived in the US 65 years late. Former Secretary of Commerce under Cristina Kirchner, Guillermo Moreno (known recently for his deceptively innovative ways to keep orthodox Peronism fresh and formerly because he would begin every negotiation with company CEOs in his office by placing a loaded .357 revolver on the desk) has expressed it over and over: Donald Trump is a Peronist. Not only that, the fact that Donald Trump was a Peronist was another piece of proof that the Peronization of the entire world is in Argentina's grasp. We've already got the Pope anyway.

It's easy to miss this idea of Donald Trump as a spearhead of social justice when all you hear during his presidency are the usual right-wing half measures and his disappointing capitulation into playing ball for the so-called swamp. But when the contemporary values of social justice are utterly relative, it is only the will of the working class who is to be respected, rejecting any and all classical labels and embracing the anti-establishment position of dismantling the pernicious institutional elements of the time. With Perón it was the Church, foreign influence and the predominant, anti-Argentine political spectrum(s) of the time: in his case, an open rejection to both fascism and communism. For Trump it was the American Government, foreign influence and the predominant anti-American political spectrum of the time, i.e. the Two Party System. Of course, one can argue that the American political spectrum wasn't anti-American, in the same way that Perón's approval of fascism nullified the accusation of fascism being "anti-Argentine" - but the rhetorical twist is even simpler: all these measures and stances are, ultimately, performed for the sake of the people. Trump, just like Perón, managed to win the hearts and minds of a social class that was despised by their countrymen and the State itself for their illiteracy and poverty and by the State itself. The main difference, of course, is that Perón's assistentialism made his purported commitment to the working class palpable, whereas it took a pandemic for Trump to start giving out stimulus checks (which, by the way, have you noticed how well these were received by marginalized groups? Black Twitter considering reelecting Trump and his stimmies was a fact too uncomfortable for many think tanks to fathom).

But now, this cycle of latency swings, again five years late, to Argentina. The Peronist formula, adapted to the Protestant gave birth to a fascinating Angloperonism that kept itself excellently in touch with the grievance of a good chunk of the American population to the point of winning an election that was all but rigged against him. Trump treaded the waters to see how many times he could compromise his core tenets without losing his voters and found that he indeed could get away with much, even a near complete reconciliation with the bipartisan system as long as he kept Hillary out of jail and AIPAC unquestioned. Five years later, the tools that helped Trump gain power finally arrived to the Argentine masses: Twitter is now essentially ubiquitous in a society that five years ago could simply not leave Facebook. In retrospect, the time felt as ripe as any to prop up any anti-establishment candidate using the same angloperonist formula. Milei has campaigned excellently through social media, taking advantage of his histrionic personality and bite-sized video edits to present his campaign platform in a concise and concrete fashion. And while any sensible person (even most who voted for him!) would find most of his campaign promises abhorrent, the novelty was the same as Trump's: being the first sufficiently loud candidate that blames the politicians for all the country's woes - something that essentially every single Argentine believes. That fact alone has placed Milei closer to the people than the strategy of larger-than-life cults of personality and dubious party loyalties. Milei (or his advisors) rejoices in copying certain aspects of American populism, no doubt due to his neoliberal fetishism, but also due to the virtues of how well neoliberal populism works in the face of a disgraced working class that were just excommunicated from the party that used to represent them. Again, Peronism does not lose 50% of its electorate that easily - it was a slow, methodical betrayal that swung the pendulum.

Milei's forte also lies in the fact that he has painstakingly explained how he intends to tow the sinking ship into the depths of the River Styx right up to the gates of hell. Very few people (even those who voted for him!) don't find his plan utterly appalling and a disgrace to popular wellbeing and national sovereignty, but it's paramount to mention that no other candidate has developed a single concrete proposal to stop the economic freefall and the danger of hyperinflation. It should be instead surprising that the Peronist candidate, the individual in charge of a juiced-up Ministry of Economy while the country was going through two-digit monthly inflation percentages, was the runner-up in the ballotage! The voter should not be punished for the common-sense idea that, if forced to vote (because voting in Argentina is mandatory by law) between a certain crash-land and the uncertainty of plunging without knowing just how deep the bottom is, one may be tempted to trust the eternal Argentine foolhardiness and opt for the former.

This sincericidal pseudo-honesty, a trait that Argentina has largely not seen in a politician in recent history, will surely be tested in the upcoming days as he begins to walk back from his more suicidal statements (negotiations and commerce with China, I'm certain, will likely begin in full force regardless of any previous statement of Milei "not negotiating with Communists") in the same way that Trump walked back from his wildest proposals; this is, after all, part of the strategy. This strategy, however, makes him an extremely predictable president in the unique circumstances he has risen to take the helm of the Executive in a country consumed by a looming threat of economic and social collapse: unlike Trump's empty platitudes of an economy in decline, Milei's shock therapy gives plenty of warning to anyone who wishes to oppose the project. It grants the opposition the invaluable privilege of being able to read Milei's game plan three or four moves ahead; it's not Milei who runs the game of ninth-dimensional chess: the chessboard is Argentina, and Milei is playing meekly, badly, by the book. Never once has a president laid his political strategy so bare; as helpful as it might have been to gather votes, it leaves him open for every organization, political party and even sole individuals to come up with a plethora of counter gambits with enough time to spare; for some of this groups, and especially for those groups who had a hand in leaving the country in the state it is, it becomes a moral and ontological imperative to read the chessboard in time before liberties are lost in the name of a meme called Libertad. To bank on the population to realize the atrocity of his proposal is to forfeit entirely, for it's after all the most invaluable tool for a populist narrative: the Argentine will not tolerate mockery after all, so it will gladly bear insurmountable hardships as long as he's

Bicycle

By Tinpanalleyscamp

Bicycle. The Queen song. I was out at the bar, telling a friend from Brazil about my project. Bicycle! Bicycle! He says, just like the song. I live in the Yukon. I have schizo-affective disorder. I'm building a bicycle. I brought it home from the dump and I work on it sometimes in the kitchen. I've got it stripped to the frame and fork and I painted it the other day. I will festoon it with Lisa Frank stickers and put it back together again with new parts. Bicycle! Bicycle! I smoke a lot of weed. I quit for a little over a year but I smoke weed again. We're doing philosophy on discord. I could rattle off a

11:30pm—Pink Flamingos

By yka, illustration of Mao by Piper Paige

The filthiest people alive!

Picture her. Tall and wide, plump. I was a fat child. Look at her; what a number dressed in gold. Auburn hair in a 60s doo. Her nipples point out, practically gilded, through her silk top. She walks demurely, purposeful…the two at her side wish that they could keep up. Fat and gold; man or woman? Auburn hair.

The filthiest people alive?

I watched a lot of weird stuff as a child. I guess a lot of us did. Not much content moderation going on. No watchful eye. Porn. Shit. Gore. All at the tip of my idiotic 11 year old fingers. Mom and dad worked late; my tayta knew no better. But where were they? Where was the V-Chip? I scan the room. No peeking.

Well, you think you know somebody filthier?

I didn’t. I don’t. I was a quiet child, nervous. Very nervous. And fat. I was a fat, nervous child. I watched the screen expectantly. A large, curvy number in gold, nipples erect, walking down Baltimore in a pillbox-looking hat and heels. Heels. I loved the heels. If I were drenched in gold, with a pillbox hat, and living in Baltimore, I, too, would wear heels. I’d even click them a few times.

Watch as Divine proves that not only is she…the filthiest person in the world…

We lived in a small house. There were no secrets…the house wasn’t large enough to hold any. My Tayta would watch my younger brother and I when my parents worked. I didn’t hear Bonanza or Matlock or loud Arabic squabbling. She was probably in the next room playing her late-night word searches or sleeping, with my brother curled in her arms…Or maybe she was about to turn the doorknob. I leaned in closer to the TV.

…she is also the filthiest actress in the world.

A dog scampers by! Cute doggie! A real bow-wow! I’m distracted by the good boy. My TV goes slightly static; I risk the sound of hitting it…

What you are about to see is the real thing.

The narration dies out…”how muuuuuuch is the doggy in the wiiiiiiindooooow?” This is the part I read about in secrecy, pored over in the school’s computer lab. I peered in close while reading and I peer in close now, watching. What I’m about to see is the real thing. The dog positions itself. “The ooooooone with the waaaaaagling taiiiiil.” He unleashes a torrent of shit. My golden goddess with the auburn hair sits down and reaches for hot shit. I lean in impossibly close; my head practically pressed against the screen. She scoops it. I gasp. She smells it. She eats it.

She eats the shit. I hear a bump outside…my heart pounds. She gags. She smiles. I want to die yet I never felt so alive. Is that the door? I am so close to the TV now I might as well turn around and say “they’re heeeeeere.” The shit presses out through the gaps in her teeth. I gag. I smile. What time is it? “How muuuuch is that dooooogy for saaaaale?” She gives one last grinning, pained look. I look right at her eyes. The screen goes black, and so do I.

Postscript: everything feels so monumental when you’re a weird little gay kid. Everything feels so taboo and glorious and deliciously depraved. I didn’t grow up in a particularly restrictive household; it was a Muslim household. A Palestinian household. A Palestinian refugee household. But not much felt off-limits, especially not as bad as racist discourses would lead you to believe. But I was nervous and fat and gay and little and arab and, again, the world always felt so illicit and monumental and delicious. So very delicious.

In my youth I would watch so many things in this self-criminalizing way. Secretary. Skinemax films. Fulci movies. I think I even watched Brokeback Mountain practically hugging the TV lest anyone catch even a glimpse at the horrors on-screen. A nervous gay little boy. But no viewing experience do I remember quite so clearly as Pink Flamingos. I had read all about it, practically memorizing the plot synopsis off of Wikipedia. The figure of Divine. The chicken. The prolapse. But nothing repulsed me so much as the description of the ending. I nervously checked out a VHS copy from Blockbuster—apathetic teenagers, not giving a fuck what somebody rents, are the truest allies to nervous, little gays. From then on, the world became that much more sick, more funny, more cruel, more free.

Years later, as both a film scholar and a much older nervous little fruit, I find many of my friends, colleagues, students, and acquaintances all share a similar story. Sometimes it’s with actual porn, other times with nothing more than a cartoon that “Mother forbade!” But these feelings of shameful intrigue, of anxious enrapture, are the things that make life seem so worth it. At least at times.

So when that golden goddess, the appropriately named Divine, scoops down and bites right into a steaming, stinking pile of dog shit, she does so not just for art. Not just for me. Or you. No, Divine eats shit for all mankind.

The Sacrifice

By Juanso de Arco

IG: @su.fortuna

juancolon2014@gmail.com

Translated from the Spanish by the author

"What is certain, however, is that, being conscious that the sacred

quality hidden in the

experience of eroticism is something impossible to reach for

language (this also is due to the

impossibility of having an experience again through language),

Bataille still expresses it in

words. It is the verbalization of a silence called God."

Yukio Mishima

The stench of incinerated corpses and bovine shit pervaded the air. The river down the incline ran black, saturated from endless ash and discarded trash. Around the edges were the niches where the families came together with their deceased, ready to offer their dead to the river goddess Ganga in the temple of Shiva. It is not without reason — the temple of Shiva Pashupatinath is the most important holy place of the god of destruction in Kathmandu. His followers in Nepal are obligated to make the pilgrimage at least once in their lives. Even from the farthest reaches of India, millions come every year, be they among the living or the dead.

Between the obvious tourists, all white people wearing shorts, and the locals, dressed casually or in elaborate local dresses, the complex was full of people. It is a large and complicated space. The lingas, phallic representations of Shiva, adorned various areas, sometimes covered by small alcoves and others exposed to the elements. Commonly made of black stone, they were never monotone, but instead always brilliant with bright red, orange, and yellow natural colorings from the faithful.

The niches which housed the lingas were always adorned with protective motifs. Among them, two stood out — Garuda and Kirtimukha. Garuda, great man-bird protector, vehicle of Vishnu, winged and fierce, yet elegant. Kirtimukha, feral beast born from the eye of Shiva. Born from the same third eye of his god to devour a man who attempted to insult him, he was stopped at the god's contrition. With the insatiable hunger of the creature being unfulfilled, Shiva ordered it to consume itself. Above almost all the temple entrances, one can see in its self destruction a conscious and fierce ouroboros of the Vedic tradition.

Penetrating deeper into the complex, passing by children, beggars, bulls, and the religious, one can see different structures near the main temple. Not everything is solely dedicated to Shiva. It is customary to have minor temples to various deities related to him. Ganesha, his son, as well as Vishnu stand out, but the majority of them are of his consort. She is represented in myriad ways as Parvati, Durga, Kali, or innumerable other tantric manifestations. One of these same structures was precisely a few steps away from the main sanctuary.

Just across the small bridge over the river lay a typical two-floor Nepali pagoda, with barely enough space for an altar inside, entrances in all four directions, and a smaller altar in front. Towards the river, a great man casually cut and cleaned the entrails of a recently slaughtered goat. The white body laid aside, the severed head being completely charred. With a swift motion of his knife, the man opened the intestines, liberating fecal liquid all over the floor. Another man hosed it down, making sure not to intervene with the organs, but nonetheless playfully wetting the man in charge of them. On the edge, towards the river, a great quantity of flying insects amassed themselves, as in almost any spot, with the difference here being the clear sight of various animal remains.

Behind the butcher stood a post, to which a black cow was tied by the neck. A black cow? No, no, a water buffalo apparently. Impossible for me to distinguish them. Inside the altar four men made dedications to an indecipherable figure in the center. They bathed it in water, milk, and rice. In unison they repeated mantras which were unintelligible to me. They didn't look like brahmins, the caste in charge of religious matters. My local friend indicated that they were of castes authorized to deal with the sacrifices to the goddess.

He didn't know what specific incarnation this minor temple was dedicated to, there being no obvious signs. The walls were decorated with the complex carvings common to these religious structures. Painted on the walls were some demigods, dancing skeletons, and uncommon figures. What he could tell me was that all the goddesses had one thing in common: blood sacrifices. Animal sacrifices weren't offered to the male gods — Shiva famously being vegetarian in his main manifestation — but the goddesses, especially the tantric ones, demanded them.

Until that moment I hadn't had much interaction with the female Hindu deities (Vedic would be a better term, as their believers properly call them and themselves). I had previously read extensively about these subjects, but much of the more intense information was scarce online. I knew of only one temple in which goats were sacrificed to Kali in Kathmandu, the local butchers doubling as priests, but nothing else. The tantric practices, between their exclusively oral and secret transmission, do not often reach Occidental knowledge outside of extravagantimaginations and notoriously elusive experts.

The previous day I had my first encounter with the commonplace animal sacrifice in the city. The former royal palace housed a temple to which buffalos were dedicated. The sacrifices were done outside, leaving the doors and walls with grave and permanent stains of blood. Hanging above the entrance were entrails of the slaughtered beasts, changed yearly. My friend Anis briefly described how these were done — the tools, the amount of animals, how some were decapitated and others had their throats slit. There’s even a southern tribe who slit the throats without any weapons, only with their teeth. Just thinking about it manifested an unpleasant feeling in my stomach.

As the days passed, it dawned on me that almost all the main temples, even down to the smallest altars in the streets, had bloodstains. Anis usually mentioned it to me at first, but I didn't take too long to get an eye for it. The blood would spurt out so intensely that it sometimes even reached the second floor. The strangest thing was finding out that the palatial temple, to which dozens of sacrifices were made, was completely empty on the inside. Only the advanced initiates could perceive what was hidden in the three floor interior. This was apparently normal in various tantric temples, with the entrances being extremely limited.

Upon leaving that area we passed through an alleyway with various restaurants, all with generic names in English. My friend complained that these keep opening for tourists and rob the city of its personality. Next to one was a small altar inside of a cage. I recognized the image on the outside. I stopped dead in my tracks as I unexpectedly found myself in front of Chhinamasta.

Among the tantric deities Chhinamasta was one of the most advanced and darkest of the Vedic tradition. She is represented as a standing woman who decapitated herself — three streams of blood spew out of her neck towards her own mouth and those of two female followers who dance at her side. With her feet she tramples a copulating couple, many times the man represented as none other than Shiva himself. From what I had read she was venerated in a limited way in Bengali communities, I had read nothing about Nepal.

Her secrets are zealously guarded and barely studied. Practices in her honor are not written down, only described as highly secretive, dark, and terrible. Initiating oneself is, besides being near impossible for most people, highly dangerous, and meditating on her is strictly forbidden for people who are not already ordained in her practices. To casually see her image in the street identifying an altar of hers — a caged and inaccessible one no less, starkly contrasting with the plethora of open altars and images all around the city — caused a sensation of fear and morbid curiosity in me.

One of the persons officiating the rituals exited the temple towards the buffalo. He untied him from the post and started moving it towards the small altar. Various men accompanied him there — all tall, some stronger than others. Casually dressed, one with PUMA sandals and sports pants, another with jeans and a generic t-shirt, dressed as they would for any normal day. With various ropes they tied the animal up in various ways.

The mouth, so it wouldn't bellow.

His front legs crossed, so it wouldn't kick.

The hind legs, the same.

The legs all together, to minimize movement and resistance, the buffalo fell to the floor with a powerful thud. Saliva poured from its closed mouth like giant mucus.

The binding movements were concise and clearly rehearsed. They were no amateurs, nor was it a task that could be done haphazardly. With this done they moved the body by the four leg knot with great ease, showing how common this was for them. One wouldn't think this animal weighed hundreds (potentially even over a thousand!) pounds—they threw it as if it was a bag of feathers. A crowd began to form, various curious onlookers approaching to see what was happening. Adults, elders, even small children heeded the call shouted out in Nepali by one of the men officiating. The white tourists, generally, were much less interested. There was hardly any space around to get a closer look. The man in charge announced they were about to commence, warning against pictures or videos, as it was a sacred act.

Two men were standing to the side of the temple with instruments. One played a percussion instrument at a constant rhythm while the other played a flute which sounded completely alien to me. On top of the altar they placed a blank paper with a drawing on it — two eyes and a third, the visage being fixed, intense, and penetrative. Two men subjugated the sacrificial buffalo while another, holding an elaborate dagger, prepared for the act.

His jeans and red shirt betrayed his clothing could, and would, be dirtied. The tika (Nepali word for the famous bindi) on his forehead was black — prepared once a year in very limited quantities by specific priests. These tikas offered total spiritual protection, kept for only the most extraordinary occasions…

Amongst the crowd I couldn't see much — the animal's head was raised and held back, grand, abysmal eyes looking around, clearly incomprehensive of what was about to befall it. Many of the animal sacrifices were simple decapitations — a weapon big enough and a person strong enough to finish the job in a single move. The ritual dagger clearly wasn't cut out for that job.

The dagger descended upon the neck of the animal, revealing below the thick layer of hair a white interior, almost like paper. I could hardly believe it was real. The hair discarded, he repeated the slash revealing what awaited — pink layers with red details. The act commenced. The drum sounded ever harder. With my vision blocked by so many people, I could hardly make out how it was developing — the buffalo's body was covered, I could sparsely see its head, its neck, the executioner, and the three-eyed paper to which the act was dedicated. The parchment began to turn red, first a soft tone comprising only a part of the paper, little by little covering more and more, ever darker. I couldn't see where it came from, but the answer was obvious. Just a few feet away, the executioner entered his fingers into the viscera of the neck — the crimson fountain ejected ever clearer towards the altar. Every time I've read or seen a representation of a throat slitting, it was an instantaneous death once the weapon crosses the neck, and this didn't seem to be the exception, the body completely immobile.

As the three eyes grew darker, their gaze became more heartrending. The man seemed frustrated — something wasn't going as expected. They needed more. The dagger went deeper into the neck as he pulled the head of the animal back more harshly towards its body. His darkened hands were bathed in blood, the only discernible attribute being a ring on his index finger with the image of Bhairava, the furious manifestation of Shiva. His enraged and demonic aspect provided divine protection during the act. The deity entered through the muscles and tendons along with the rest of the fingers. In that moment my gaze couldn't perceive anything besides that ring, the entrails, and the blood spurting all over the floor, the man with his knee on the animal. The percussion marked the anxious beating of my heart. I moved my eyes and clearly saw the head of the animal.

It's alive. Dear God, it's alive. I see its eyes, window of panic and desperation, and it's alive.

I instinctively covered my mouth which hung open, refusing to close. The beast attempted to escape, resisting, roaring, and moving its body. Between so many tightened ropes and men holding it down with all their weight, the attempts were in vain. The knife kept going into its neck, each time more and more blood came out. The three eyes kept accepting this sacrifice which began to spread through all the altar and even into the temple. A beast of such size had more than enough blood for the occasion, spurting without mercy in all directions. The dagger could do nothing more than keep penetrating, its movement as jagged as a saw. Halfway through the neck the man was able to cleave effortlessly through veins and cartilage. Halfway through the neck the beast's resistance expired. With a final outbreak of blood he definitively amputated the head, lifting it as a trophy. The drums lowered in intensity until arriving at silence. The act had ended.

The people started going their own ways to go on with their lives. The wandering salespeople resumed their harassment of the tourists. The ones who committed the sacrifice moved the corpse to be cleansed, the head placed atop the altar, followed by the rest of the less impressive rituals. The elderly talked amongst themselves as if nothing had happened. The kids ran to play somewhere else. The families continued to the main temple. A gringo comforted his spouse, visibly shaken by the act of cultural immersion. Anis casually asked me if I had a good time. I wasn't sure. It wasn't the first time I saw an animal die, not even violently, but this occasion had a very different tone to it, much darker than anything else I had witnessed.

My friend, being a Buddhist of the local Newari tradition, told me that the followers of Buddha don't believe in animal sacrifice as they don't support violence against any living being. The substitute they use for their tantric rituals is eggs. Regardless, animal sacrifice is so frequent in Kathmandu that he was far from being affected by what took place. The general belief is that the souls of sacrificed animals escape the cycle of rebirth and go to paradise. He still made sure to tell me that not all Nepali people see and accept these practices without giving it any thought. There are organizations against violence towards animals, the Supreme Court of Nepal once even attempted prohibiting these practices before a massacre of hundreds of animals celebrated annually for a festival. The religious groups do not permit these rites to be halted. Any legal consequence they could incur for this is nothing compared to invoking the wrath of their tantric gods and goddesses. The image of Bhairava, with his furious countenance and his sword covered in blood, made this very clear.

A few days afterwards, in a nearby Buddhist jewelry store, I peeped at the rings and saw two marvelous examples. Kirtimukha and a furious protective deity. Donning a crown of five skulls, a third eye, and with teeth protruding from his mouth, I couldn't help but remember the Bhairava ring. It was Mahakala, the furious Buddhist representation of Shiva. The memory of the blood, of the neck little by little disconnecting itself, and the animal still alive all pervaded inside me, ingraining a profound sense of terror. How could I possibly return home after witnessing such a thing? Nothing felt quite the same for the next few days. Kirtimukha gazes upon me from my finger, knowing there's no way back.

Lost in Translation

By Jigme

There is a dilemma that has plagued Western university classics departments for some time—how does one accurately translate Latin poetry when it so often offends our “classical” sensibilities? This issue becomes pronounced when we look at the common English translations of the erotic and humorous poems of the Carmina Priapeia.One of the earliest complete translations of this work of poems dedicated to Priapus, the Roman phallic god, was done by Leonard Smithers and Sir Richard Burton in the late 19th century. Despite being how most anglophones will probably encounter these poems the translation leaves much to be desired in terms of content, in spite of how good the prose may be. Take for example the third poem of the collection (which is listed as “Poem 2” in the Smithers text). The poem is one of erotic desire for the narrator’s partner. It is, to be blunt, very horny. Now Smithers and Burton do a fair enough job translating the first eight lines of the poem (enough so that I do not feel the need to interrogate them here at least) but their English prudishness subverts their abilities in the last two lines.

simplicius multo est 'da pedicare' Latine

dicere: quid faciam? crassa Minerva mea est.

These lines are translated as:

Simpler far to declare in our Latin, Lend me thy buttocks;

What shall I say to thee else? Dull's the Minerva of me.

Our Latin readers will immediately see the problem here. To be blunt again, that simply isn't what is written. There are two significant problems here. The first of which is quite obvious; “da pedicare” is extremely vulgar. Perhaps to Smithers and Burton “Lend me thy buttocks” was the height of dirty talk, but to modern terms: the narrator is asking his partner, in a vulgar manner, for anal intercourse.

The issue with the last line is unfortunately a bit more complicated. “Crassa Minerva mea est” is a pun. Anyone who has done translations in the past knows that puns can oftentimes be near impossible to translate properly. In this case the adjective “crassus” is doing double duty. On the one hand it means “thick.” A “fat minerva” was an expression in Latin that would mean something along the lines of rustic or common2. The other meaning of the word here is “audacious” which in this context carries an erotic connotation.

To be fair to Smithers and Burton I don't think they had the proper language at the time to translate this line, but I believe we do now. If you would indulge me here is how I would translate this difficult passage:

It is much simpler to say, in plain Latin, “let me fuck you in the ass!”

How else should I say it? My Minerva is rather thicc.

a

Kant's Schizophrenic Interrogator, Mirecea Cartarescu

By Regine Olsen

As much as Kant, the last great philosopher in the classical sense, closed off philosophy to direct experience of reality with the Critique of Pure Reason, his restoration of metaphysics to the “Queen of the Sciences” leaves a profound hole within “purely” “rational” comprehensions of “reality”. Insofar as direct knowledge of things in themselves has been closed off by Kant, I was always struck how explicitly Kant filled this gap in the epistemological unity of reality with “faith”: “I have…found it necessary to deny knowledge, in order to make room for faith.” We can know that scientific truths are true for us in an intersubjective, empirical nature – but the extent to which metaphysical claims have any truth beyond this epistemological bracket leaves any meaty claim about reality, negative or positive, on extremely fragile ground. Reality in secular western epistemes, since Kant, is post-truth, as any cursory look towards the metanarratives that permeate political, social, and popular discourses proves out. Faith in the truth of our experiences and beliefs largely provide the epistemological support for society itself, for better or worse. Faith is the indelible aspect to metaphysics, and grounds what is real to us for our personal realities, from the most banal, to the most schizophrenic.This crux between the reality of our reality, and the ability for faith to substantiate our reality, along with the possibility of our agency to have any say towards these inter-negotiations, stands as to me one of the most sublime themes in the fictional works by Romanian poet, author, and philosopher, Mircea Cartarescu. The haphazard, whimsical, horrifying, and truly sublime stories found in his novels Nostalgia and Solenoid will prove to be landmarks in contemporary literature, as they interrogate the recountings of fictional(?) memories from his childhood and experiences as a teacher in the public educational system, the uncanny constantly finds itself upending, poking through, and exploding from within a clear understanding of even the simplest truths of his own life. An attempt to uncover the debaucheries of his students in a local factory uncovers a terrifyingly beautiful museum of gargantuan insects only witnessed in the works of Lovecraft. In another story, a man’s obsession with the sound of his car horn ultimately leads to him physically and spiritually subsuming and becoming all of reality of the universe. Or yet again, a protest against death results in an inexplicable and deadly confrontation with the Gods – all meanwhile Cartarescu’s main characters go about their days blindly scouring the infinite halls of their school to find their homeroom classroom, and going home to his boat shaped house where he sleeps in a levitating bed. I cannot summarize these stories to make them more comprehensible– you will have to experience them by reading these books.

One critic has described Solenoid as “the best surrealist novel ever written” – the strangeness of Cartarescu’s episodes prove to be electrifying in themselves, but the kernel of truth that makes them so compelling is the philosophical backdrop upon which they rest. The empirical is always permeated by the unreal, or by a reality more real than reality itself: “This is what my life is like…the singular, uniform, and tangible world on one side of the coin, and the secret, private, phantasmagoric world of my mind’s dreams on the other side”. “Facts” for Cartarescu are “ghostly and transparent and undecidable, but never unreal”. Thus, as the narrators of Cartarescu’s works traverse multiple realities, biomes, memories, and conspiracies that rival the greatest of humanity’s gnostics and epileptics, Cartarescu uncovers the radical freedom that lies beneath any ostensibly banal notion of truth.

For Cartarescu, reality is truly unhinged from itself. Scientific truths are truth until they are not (for the truth of this, one can also refer to the life of Copernicus…). As much as Cartarescu’s “grey” Bucharest, “the saddest city in the world” draws Kafka for its bureaucratic hellishness, one cannot ignore the colorful efflorescence of Cartarescu’s world (Cartarescu sees himself as a Gregor Samsa of sorts: “I was an innocent, velvet butterfly with feathered antennae and plush white wings, immaculate, bound inside the dense horror of a spider’s web”). As much as fear and pain are essential aspects to human being, beauty itself continually pries itself out of the bureaucracy of our ontology. The world is not “darkness” but a “baffling flutter of light and shadows”, and it is this beauty, as with the torture of being, that Cartarescu is impelled to project from “the infinite and infinitely stratified and infinitely glorious and infinitely demented citadel of my mind”. For Cartarescu, every moment is a “fork in the road”, and no aspect of reality is a dead end. As such, his work stands as both a repudiation and confirmation of Kant’s rigorously dry and absolutely open metaphysics. It is here that we also find the truth of Hegel’s co-opting of the Kantian critique, in commonality with Cartarescu.

In the truth of our divorce from the thing in itself, we find the absolute truth of our world: its inherent instability – that we ultimately know nothing of truth. For Hegel, truth is a process, and continually, in every moment, being uncovered, instantiated, and made true. Truth is dynamic, which Catherine Malabou has enshrined in her concept in “plasticity” in The Future of Hegel. In such a world, the future is perversely open-ended, in every possible direction: “to posit the future as ‘plasticity’ amounts to displacing the established definition of the future as a moment of time…’the future’, that which is ‘to come’, will not be restricted in meaning by the immediate”. Can there be a future where one plays a game of russian roulette with a gun loaded with a bullet in every chamber, and still live? One will have to read the first short story in Hegel’s reading of Kant, there is more than one future for such a game.

Cartarescu’s work attempts to present a view of “life without the reality-validating mechanism,” or in other words, so doing, he presents a world that is perhaps “insane and misguided…[but] in the end it contains truths”. In a similarly perverse reading of Kant's first Critique, we also find an insane and unstable world – and yet though unstable, Kant’s world is still yet true – the work of Cartarescu serves to interrogate our post-Kantian world.

The Retention Review is a zine brought to you by The Academy of Philosophical Cultivation and Retention. Through our principles of democratic participation in philosophy and our dedication to not being too serious, we hope to provide a platform for those outside academia to "do philosophy"

If you have any questions, comments, or would like to participate, please email us at editor@aopcar.com

Community

Please join us on Facebook, Instagram, or on Discord.